One Liners, and many other wonderful things, may be purchased at the Springtide Press website. Spring's Instagram handle is @springtidepress

Although I’ve spent a lot of time working with and designing typefaces, I’m not one of those people who’s just crazy for type specimens. I like them well enough but very few of them make me all squishy inside. I think this has to do with the fact that my love of type grew out of my obsession with printing books. The type specimens that I have to have either feature a meaningful textual content and/or display virtuosic feats of printing (think Jen Farrell's The City is My Religion or Charles Derrier's Specimen-Album). All those other specimens—the kinds that show a zillion variations of the same face or just display their types in nonsensical texts—send me daydreaming. They’re fun to look at, but as a book lover they leave me wanting more. I guess this makes me more of a type crank than a type geek.

Of the type specimens I find least inspiring, none rival the one-liners, those numerical listings of typefaces in which the type on display may as well be widgets in a trade catalog. Sure, this one is heavier, that one slimmer; this one shouts, the other murmurs; but at the end of the day the types just stand there, lined up like bored suburbanites waiting for their trains. When I look through these books, I feel as though I’m suddenly a middle manager whose sole job is to decide what titling type pairs well with Text Type #35. Fancy a swash perhaps? No, I better not….

It's funny what books reveal about their readers. What kind of nut job feels reduced to a suburban middle manager by a type specimen? Aren’t the minute details that distinguish one type from another—the very details that should matter to someone who loves type—easier to appreciate in one-line specimens? Must everything be a grand spectacle, clanging along with maximum bells and whistles? Well, in answer: 1) my kind of nut job, 2) yes, and 3) why not? If one-line specimens are what’s available, I want one that’s firing on all cylinders. I want it to be literate, geeky, and dazzling all at the same time. And I don’t think that’s too much to ask, even though I know of only one book that fits the bill: Springtide Press’ One Liners.

I became aware of Jessica Spring’s work via the circuitous route of a hashtag: #daredeviltypesetting. A lot of metal type printers on social media tag their posts as “daredevil,” and eventually I followed the trail to its source: Springtide Press’ Daredevil Furniture. I started following Spring’s Instagram feed and, with each post, my retroactive FoMO grew more intense.

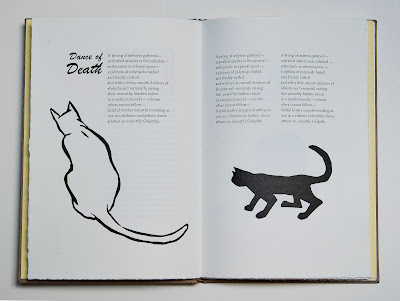

Spring is an aficionada and collector of historic typefaces which she uses with an intelligent, iconoclastic wit. She makes, among other things, precise, postage stamp-sized “seals of approval”; political broadsides; conceptual artists’ books; and self-styled “daredevil” typographic prints. Spring and I began exchanging prints now and then, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. With each exchange, I felt like I got the better end of the deal. Spring’s prints are more elaborate than the blunt missives that I typically send out. They are also more nuanced. There is an historical intelligence to Spring’s designs—she doesn’t simply revel in the profusion of material available to her (though she undoubtedly does do that), she uses that material in deliberate, meaningful ways. She also seems to have a lot of fun doing it. To describe her work with any kind of accuracy requires a flurry of adjectives; her work is quiet, loud, restrained, brash, clever, timely, historically-minded, and many other things besides. All of these qualities are present in One Liners.

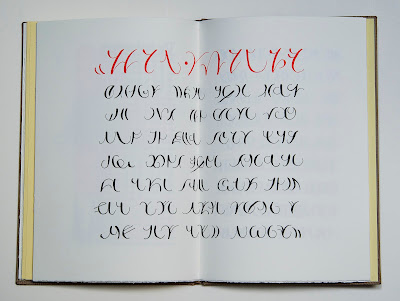

One Liners is half specimen, half journal. Or, actually, it’s whole specimen, whole journal. It consists of one line of type that Spring set every day between January 1, 2021 and April 6, 2022, with an appendix of monograms and initials that were set later. As Spring writes in the introduction, “…I would set just one daily line measuring 22 picas…. My intent was to capture each day, from the most mundane and personal to events unfolding in the world. There was no lack of content: on day six our nation’s Capital was attacked by a violent mob. The insanity continued with Covid, political protests, environmental catastrophes, and the death of my dear friend Pat.” The opening page of One Liners reads:

A resolution made: set forth & print

When the days run together, it’s Blursday

Sunday Family Zoom

Georgia votes tomorrow!

COVID 19

We win Georgia, but lose the Capitol to terrorist mob

IMPEACH

This is America. This has always been America… Let it move us to action –R. Gay

Seeing friends and family virtually leaves me anxious, lacking

No rain? Let’s walk.

Please, please—stop saying SILVER LINING or ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

What Spring captures in her one-line journal entries is the different structure of Covid-time, particularly the strange equivalency of events—any events—during the lockdown. Anything that pierced the otherwise plodding sameness of the day, the week, the month is in this book, and, when I read it, I feel as though a little of my humanity is being restored. The constant torrent of the 24-hour-Covid-Police-Brutality-Insurrection news cycle is there. But so are the aspects of life that are ordinarily granted less weight, like a Sunday family zoom call, as well as the loneliness and anxiety that such a call can provoke. By including these “lesser,” personal events alongside the global issues of the day, Spring elevates them to the status that they deserve. It is precisely these quotidian moments that I want to remember.

As life has gradually returned to “normal,” my experience of time is once again the amorphous wash by which pre-Covid life was recorded. Life has become fast and full again. And the default judgements of an informationally-fatigued populace—baking bread = banal, political scandal = meaningful; or, personal loss < global strife—have returned in their ambivalence-inducing bias toward the sensational. When I sit and read One Liners, as I have done many times, it helps me fend off this diminishment of the personal. In other words, it does exactly the opposite of what I accused one-line specimens of doing a few paragraphs back.

One Liners does all of this while displaying Spring's remarkable collection of metal type. It is enough to make even the crankiest type lover pine with envy. One reality of stewarding such a collection is that the type is both precious and delicate. It needs to be handled with care. This kind of handling has resulted in occasional uneven inking, which is One Liners' single, minor flaw. But as a printer, I would turn that statement upside down: the fact that the printing is as even as it is, considering the light impression used to protect the type, is further evidence of Spring’s talent.

One Liners is a book that can satisfy all manner of type-crazed bibliophiles. If metal type is your thing, this book has it in spades. If you find solace in Covid memoirs, One Liners has you covered. If you belong to that super-niche fellowship for whom 22 pica lines form the godhead, look no further. Most of all, One Liners achieves what I consider the highest goal of book arts: to make a book in which the textual and graphic content fuse into a greater whole. It is through this elusive alchemy that a one-line type specimen can change the way I look at the world and how I want to live in it.

* All photos courtesy of Jessica Spring, except the one of the Schriftguss specimen which is by Annie Schlechter.