Multimedia woodcut by Nancy Loeber.

Nancy Loeber and I met at the Center for Book Arts in 2001. We found ourselves working side by side one afternoon and when I asked Nancy what she did, she said she made “gouache paintings.” It was an unusual answer that happened to fit a problem I was having with one of my books. I was in the midst of producing ten manuscript copies of a geometric alphabet, in which the letters were drawn in pencil, watercolor, and India ink. The resulting outlines were then filled-in with black gouache. The drawing part came naturally to me but I was struggling to stay within the lines with my paint brush. When I asked Nancy if she was able to paint within the lines, her response was so self-assured that I was soon delivering batches of drawings for her to paint. By 2003 Nancy was cranking a Vandercook at my job printing business and, until 2018, she worked for me off and on in a variety of capacities. Without her help many of my most ambitious books would not have been made.

As I’ve gotten to know Nancy, I’ve learned how unsatisfactory an answer “gouache painting” was for what she does as an artist. Her work defies categorization. She draws, paints, collages, sculpts, writes, sews, knits, crochets, quilts, makes stop motion animations, binds books, and, of course, she prints. She undoubtedly does other things besides. Watching her work from day to day, year to year is constantly surprising. At any given moment Nancy might be making reduction woodcuts, a series of quilts or patchwork collars, or a pair of conjoined stuffed animals. What unifies Nancy’s work is her inimitable sensibility. Displayed next to each other, the siloed categories into which her works would normally be placed disappear.

A quilt in progress, a collar, and a conjoined pair of bunny rabbits.

Despite Nancy’s training as a printer and bookbinder it took her a while before she published her first editioned book, Nine Ladies, in 2014. Since then, she has published seven additional letterpress-printed books and two indigo-printed zines, as well as many stand-alone prints. All but one of Nancy’s books deal with portraiture as their primary imagery, but it is the changes and developments between her books that makes surveying her overall output illuminating.

Nine Ladies is a deceptively simple book composed of woodcut portraits. The “ladies” rise up from the bottom of the page, or hover in the middle, or are hemmed in by blocks of color. Most wear inscrutable expressions. Some are ghostly, others stare straight at you with a disarming frankness. While paging through the book, it is hard not to feel like you’ve met one of these women before. From the printing perspective, the portraits evoke a painterly quality, down to the smallest details. More than one woman’s eyeball required printing four colors, others needed just one. All are equally evocative.

Love Song, 2015, doubles down on the color printing in Nine Ladies, pushing it further than seemed possible. The portraits are stunning in the minutiae of their detail and in Nancy’s unexpected and brilliant color choices. Love Song also introduced three elements that were not present in Nine Ladies: a dedication, “to William/and all the sinners;” a text, the poem, “Annunciation,” by Marie Howe; and deliberate pacing achieved by the use of a small, ornamental image that acts as a pause between sections of portraits. Though ostensibly similar to Nine Ladies—it’s a book of nine woodcut portraits—Love Song is considerably more complex.

Color woodcuts from Love Song.

All except one of Nancy’s books since Love Song have featured a text, and the texts she chooses are further expressions of her sensibility. In 2016 she produced an edition of George Green’s poem, “Lord Byron’s Foot,” a hilarious romp through Byron’s biography that focuses on the poet’s lame foot as a means of knocking him down a peg. The portraits here are in service to the text and the book’s layout is the first of Nancy’s to use the two-page spread to advantage, text on verso, image on facing recto. The interplay between the two is the most traditional in any of her books but, as with anything Nancy makes, tradition is merely a starting point from which she departs on her own, unique trajectory.

One of the distinguishing characteristics of Nancy’s drawing style is the inclusion of collage elements. Some of the woodcuts in Love Song and “Lord Byron’s Foot” feature women with ornamental shapes in their hair, like wreaths or dots, that allude to this style but don’t quite capture it. In 2017, Nancy published four books—Brother Sister, Sticks, Drugs & Feelings, and Land Shark—each of which explored new ground. Together they began to blur the barrier between Nancy’s drawing and printing styles, pointing her in the direction that she continues to explore today.

Two spreads from Lord Byron's Foot.

Brother Sister is comprised of six woodcut portraits, printed in three pairs on unbound bifolia: a sister and a brother, two brothers, two sisters. Nancy wrote the text, which beautifully captures both teenage life in the late 70s/early 80s and the mixture of love, resentment, and concern between siblings.

Land Shark and Drugs & Feelings were both printed by indigo, allowing for photographic reproduction of Nancy’s collages and drawings. Land Shark is purely visual, using cuttings from a coloring book as material for collages, while Drugs & Feelings combines Nancy’s poems from the 1990s with her mixed-media portraits of six women. The sheets in Drugs & Feelings are unbound and folded in quarters. The poems are haunting, drug-fueled rambles that are enlarged from their typewritten originals. The exaggerated size of the type adds to the strangeness and slight menace of the texts. They are hard to read but impossible to ignore. Interleaved within these are the six portraits, all striking in their combination of precise draughtsmanship and collage.

Multimedia drawing of Vanessa Bell from Drugs & Feelings.

In her edition of George Saunders’ story, “Sticks,” Nancy brought this approach to portraiture into her letterpress books for the first time. The three woodcut portraits in Sticks are as vivid as ever, and each is festooned, embellished, completed (choose your verb) with collaged elements that create a telescoping effect. The combination of woodcut and collage gives a heightened dimensionality to the prints that takes them into another category altogether.

Page spread from Sticks.

The books Nancy has made since Sticks continue to draw on her diverse array of talents. In her edition of Jane Bowles’ story, “A Stick of Green Candy,” 2019, Nancy continued her mixed-media printmaking approach by using woodcut, collage, found imagery, and gouache.

Page spread with multimedia woodcut from A Stick of Green Candy.

Nancy illustrated her edition of Bowles’ story, “Andrew,” 2021, with prints, sculpture, and found objects. “Andrew” tells the story of a young, emotionally-stunted soldier who feels “as though his face were made of marble,” and who falls in love with another soldier who, among other things, likes sparklers. The book features a series of multi-media prints and is housed in a partitioned box that holds twelve sparklers and two hand puppets constructed from crocheted linen and cast, marble-like plaster.

Multimedia print and box from Andrew.

One of the aspects of Nancy’s books that I find most interesting is how closely aligned her artwork is with the poems and stories she chooses to print. The texts by George Green, Jane Bowles, and George Saunders all embody a similar sense of adjacency as Nancy’s art. They are serious, meticulously crafted, and slightly (or significantly) off-center.

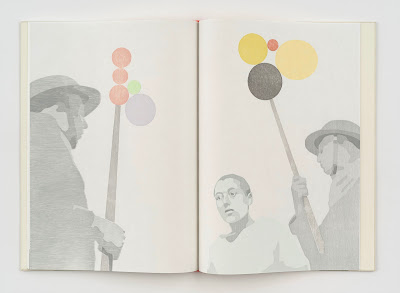

This quality continues in her two most recent books, Radical Tenderness Manifesto by Dani D’Emilia and Daniel B. Chávez, and This Person by Miranda July. The images in the Manifesto are inspired by stills from Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 film, The Passion of Joan of Arc, but Nancy has replaced the lethal ends of the weapons with brightly colored balls. The portraits in This Person are placed within a subtle ombré of color and garlanded with ribbons.

Two spreads from Radical Tenderness Manifesto.

Considering the intimate comingling of textual and visual content in Nancy's books, I sometimes wish she would be more adventurous with her typography. But when I step back and look at the unique body of work she has

produced, I would hate to think of her changing anything at all. What makes Nancy's books (and quilts, and pillows, and bunny rabbits) so wonderful is that they grow out of a personal vision that cannot be contained. This is abundantly obvious when I've seen her cutting woodblocks—her focus and determination is remarkable. The books that she makes with that focus might fall within the community of artists' books but they are unlike anything else you will find there.